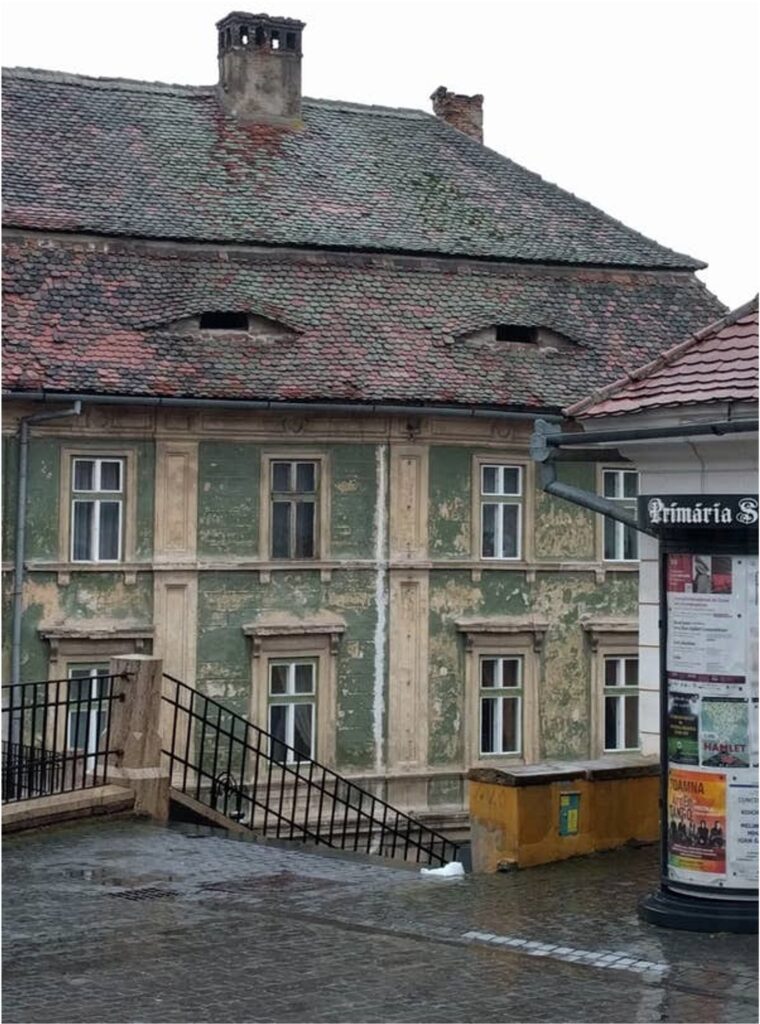

Let’s start with something strange.

Have you ever looked into a plughole and seen an eye staring back? Or paused, for just a moment, because a tree stump looked oddly… like an owl?

It’s not just you.

Humans are wired to find meaning—faces, emotions, even motives—in things that are entirely inanimate. It’s a phenomenon known as pareidolia. And it’s one of the earliest clues into how powerful our instinct is to see story in everything.

A Circle, a Triangle… and a Chase Scene

Back in 1944, psychologists Fritz Heider and Marianne Simmel ran a now-famous experiment. They showed people a silent animation of geometric shapes moving around a screen. That’s it. No dialogue. No context.

But what people described?

A dramatic scene of conflict and rescue. Two men fighting over a woman. A frightened child. Rage. Guilt. Innocence.

It revealed something fundamental: we impose narrative on chaos. We’re meaning-making machines. And that’s not just quaint—it’s strategic.

The Hollywood Secret: Why Every Blockbuster Feels the Same (And That’s the Point)

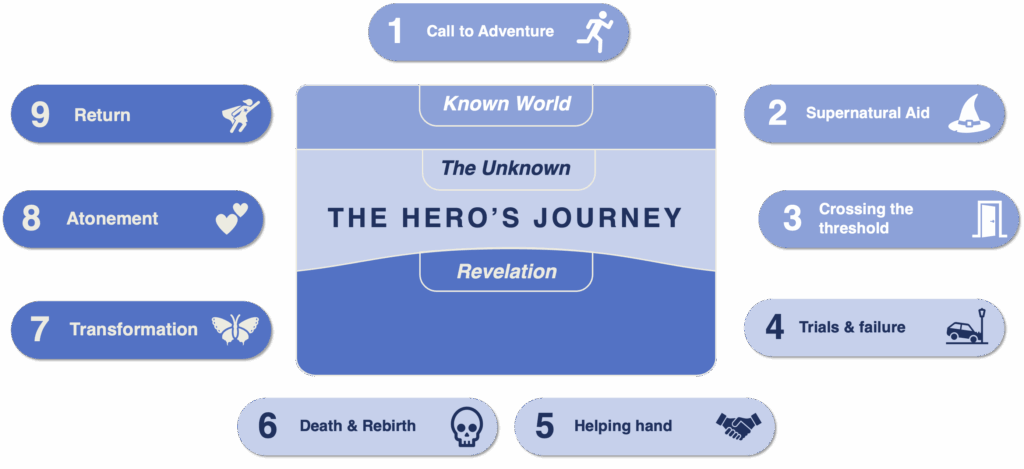

There’s a reason why The Matrix, Barbie, Harry Potter, and Star Wars all feel strangely familiar. They’re using the same playbook.

Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) was the breakthrough. He identified a universal pattern that runs through mythology across cultures, later adapted into what we now call The Hero’s Journey.

Hollywood took note. George Lucas famously credited Campbell’s work as the blueprint for Star Wars. Pixar formalised it. Screenwriting handbooks immortalised it.

And the structure stuck. It works because it mirrors how we experience change in our own lives. Good fiction isn’t just invented, it reflects something we already feel. Something true.

Which is also why it works in business.

The Buyer Is the Hero, Not You

Enable doesn’t just use this structure for storytelling. We use it to reframe how our clients win. In procurement, the buyer is the one on the journey. They’re the one facing pressure, risk, and ambiguity.

If your proposal, pitch, or message doesn’t help them feel like they’re making a brave, smart, meaningful choice, you’ll be forgotten. Or worse, disqualified.

So we build your messaging as if it’s their story.

Because, biologically speaking, that’s the only story they’re truly interested in.

The Biology of Story: Why Brains Love a Good Arc

Dr Paul Zak, a pioneer in neuroeconomics, has proven something storytellers instinctively knew:

Stories change us at a biological level.

Zak’s studies found that compelling narratives increase the brain’s production of:

- Cortisol, which captures attention

- Oxytocin, which increases empathy and trust

- Dopamine, which reinforces memory and motivates action

In one of his studies, people who watched a moving story with a clear beginning, conflict, and resolution were more likely to donate to charity afterwards (Zak, 2015). Not because they were manipulated, but because they were neurologically engaged.

His term for it? “Narrative transportation.”

When you’re in the story, you’re less resistant. More open. More trusting. And more likely to act.

This isn’t about being emotional for emotion’s sake.

It’s about using what biology is already doing, to guide decisions more effectively.

What This Means for You

If you’re selling, bidding, influencing or seeking strategic change—here’s the simple truth:

Facts matter, but feelings decide.

Data doesn’t win deals.

Narrative does.

But only if the story is about them, not you.

So here’s the practical next step:

Reframe your strategy and sales materials through the lens of the Hero’s Journey. Position yourself not as the hero—but as the guide. The mentor. The one who helps them win.

Because in the end, influence doesn’t come from being impressive.

It comes from helping someone feel like the right choice was always theirs.

Want to Build a High-Impact Narrative Strategy?

We help ambitious organisations land critical wins by reshaping how they influence.

Let’s talk.

References (Harvard Style)

Campbell, J., 1949. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press.

Heider, F. and Simmel, M., 1944. An Experimental Study of Apparent Behaviour. The American Journal of Psychology, 57(2), pp.243–259.

Zak, P.J., 2015. Why Inspiring Stories Make Us React: The Neuroscience of Narrative. [online] Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2015/10/why-inspiring-stories-make-us-react-the-neuroscience-of-narrative.